Riot in the highlands

by

Megan Wildhood

excerpt from a work in progress

Our body spun on a bed under a stationary ceiling fan encircled by white Christmas-tree lights. Watching it made us motion sick for the first time in our life—was it our body that was spinning, or our mind? We saw our body below from the ceiling. Our neck felt like a singular, swollen joint. A machine (labeled PROPERTY OF KING WEST MED CENTER—EXAM ROOM 7 in handwritten block letters just above its spECTrum 5000Q—MECTA Corp. embossment) hissed near our ear, like it was making secrets with the bed-table propping us up. An angel lifted off from a Christmas tree and burst into bright ash as it arced over us. We instinctively tried to tuck and cover, but one wrist and one ankle met harsh resistance and stayed pinned to the bed.

Being in two-point restraints at King West Medical Center pretty much means only one thing: involuntary commitment to the psych ward.

A large buzz hummed in the background of everywhere. We looked down and realized we could look down—we were not outside on the ground, we were not trash in a dumpster. The amount of joy that flooded us—we were not outside! We wanted to sing as we flew around the room—was almost enough to ground us back into our body. Don’t give them any more reasons to think you should be here, dear. The angry white was not the rare bird of snow but tile. An angular man passed by on a carousel made of paper cups and yellowed wallpaper. A dryer turned like it was nauseous. A fridge muttered like an empty stomach. A fridge! The back of our skull felt missing. Most other objects were too small or too large to be seen. We tasted clay. The fan started to move, slicing dark into thick belts.

***

“Your husband was perfect.” It’s only okay that Cyan says this so soon, the same day of Porter’s death, because she’s been our best friend since kindergarten.

***

A man in a lab coat walked into the room, which was so white it would show any iota of dirt. A door swiveled open to let in people made of parchment dressed like TV doctors. Our neck loosened. Pebbles dropped from our ears and rolled around in our neck. The side of our head filled with a lively pain. One doctor said our name, but his voice sounded like it had to get through water. What he said wasn’t to us. “This is enough for today. She’s quieted down nicely.” The words moved in pieces. The buzz softened but pressurized, like it had been stuffed into our mind. His pointy fingers prodded the goose egg on the very center of the top of our head. The hole in the middle of our brain, which also felt like it was in the middle of our heart, was new, too. Things were falling into our eyes as we looked at them, faster than our brain could name them.

We could not raise our arms or bend them. Same with our legs. Our head was flopping side to side without direction from inside it. This was not exhaustion. Cold, hard bands clamped our wrists and ankles to within an inch of the table. The pillow smelled like burnt sage and cedar as it started to swallow our head. A crack started in the ceiling, splintered into a million more.

The man and a nurse start-stopped around the room like an old movie reel. They took our fingerprints and scanned our retinas and led us, still lying down, to a 5.11-story building adorned with our auburn hair and our wide hips. The top floors looked to be separating from the body of the structure. It wore our old uniform: a V-neck, navy-blue sweater vest with “Metro Transit” sewn in thick red thread over a T-shirt, stiff green in need of a stiff drink, and starched navy pants. Its wrist was wrapped hard in medical gauze. We entered through a latched gash we didn’t know we had in the right toe (not the one with the missing nail). Once the door closed, it sounded like a mass shooting in an amphitheater: more construction than around the city of Seattle. A staff member switched on a gas lantern and guided us up what turned out to be a long, steep flight of stairs.

***

“Photovoltaic,” Hannelore says, sitting on the orange couch with Lisa. Cyan stands closer and closer to us. Lisa hinges her face toward Hannelore with her jaw; her eyes—the same color as her hair before she dyed it black—stay on Cyan. Hannelore breathes slowly, trying to be silent like she feels guilty she can breathe, darting her gaze between Cyan, Lisa, and the widow. We are the widow. We are not the person who was friends with Hannelore, Cyan, and Lisa for all those years before they went off to live real lives. We are no longer that person, but they, just like Porter, left first. They all left first.

***

The whole building lurched as we passed through a hallway that seemed like a morgue and smelled like lemon. The passageway narrowed in places where the walls became swollen, and ended in a right angle at an ankle where the stairs were stiff. We had to cross over another hinge point at the knee, enlarged and shouting red, as the staircase widened and the rush of strong rivers flushed past us all around, whooshing like speeding buses crossing a bridge.

We climbed behind the presumed doctor and the nurse to where a stomach should have been. Just darkness so black it was blue. So black that light could not escape. An orange-clad construction crew exchanged this dark for seething flesh, piece by piece; the smell of Cheetos seized our saliva glands and panged in our jaw. Hunger like a gong doubled most of us over. The fibers of the new stomach had no substance; they could hold almost nothing except stories of holding almost nothing.

***

The police cut down the body. It doesn’t end its ending. The officer who catches it grunts like it weighs something. But it is made of gauze.

***

The brusque tick of an old-timey movie projector on the pistoning crimson above the stomach made us twitch. Amanda, eight, rifles through boxes our parents labeled “storage.” No food in the boxes. Amanda tosses their contents onto the living room floor and cries too loudly not to get in trouble. Our arms and hands and stomach and butt tensed up as we struggled to stack them, hoping to avoid punishment ourself. Neither parent comes. We find a purple and gold photo album, blue and pink and yellow flowers drawn on it with chalk, maybe; A Girl and Her Vacations calligraphed across the top of the cover. The back half of the book is empty; the front half has us with Amanda, Mom, Dad and, at the very beginning, Beauty, our beloved black boxer. Cyan came with us to the beach that day. Hannelore finally got into a tent with us. Lisa captured it. Hannelore’s eyes were so green it’s a wonder everything she looked at wasn’t the same color. How we got a copy of that photo isn’t documented anywhere, internal or external. Several shots of the four of us at various ages, outside under a trellised lamentation of clouds. A shot of Amanda’s hand connected to Dad’s hand connected to Mom’s shoulders connected to strong arms connected to our left hand, which the juvenile RA had already started to colonize. The edges of the photos, of the album, of the room, are all beginning to melt like wax.

***

Six inches from our nose, stomach fibers twisted and tightened. There was no memory of this. “Don’t worry, many memories are stored in the brain, too,” the nurse said, hovering above us in immaculate heels that could aerate a crop field. “We can search there, too, when we get there.” Her voice was too gelatinous for her stringy body. Her three-point hat cast a chilling shadow of a human with an insufficient head.

***

If Porter wrote a note, it is never found.

***

Our stomach churned through acid like Amanda through boxes. “It’s okay to not remember,” the doctor said, measuring and muttering.

Sand poured down the stairs. We’d spent significant time at a beach only once: with Cyan, the stressfully loud and relentless ocean, the messy piles of long-dead trees, seaweed slick as ice; how sand held the sun long after the day buckled. The sand falling down our knees was red and white and hotter than any day could have made it, no matter how immortal that day was in our mind.

“Have you ever seen that photo album before?” The doctor pointed into a new scene (a wedding album?), white with rhinestones and multicolored seed beads splattered in the right corner and all along the spine. “Family vacation seems unlikely, yes,” the nurse nodded and wrote something on a legal pad pinned to a clipboard in her hand. We hadn’t said anything out loud, we thought. “Correct.” The doctor clicked his tongue. The whole building spasmed again.

We trudged up more stairs, passed the black hole that had to be deeper than the building. We saw the light, thick as water, before we turned the corner to the last flight on this level: the central hub of the building. Doors slammed rhythmically somewhere close, which was oddly soothing, the way human sounds are at night when you think you’re alone and don’t want to be. Several shadows—some actual monsters, some with Amanda’s face or Cyan’s voice or Lisa’s hugs or Hannelore’s latent lost shit— flitted by and we felt it in our heart.

“It looks like the voltage I guessed wasn’t too far off.” The doctor tapped a pencil on the edge of a clipboard. “By keeping the light thick,” the doctor said, “we ensure buoyancy in the heart and mind.”

“Essential to recovery,” the nurse said like it was a recording the two of them made long ago.

“Many people undergoing mental collapse find they can’t eat or don’t wish to,” the doctor said.

“By creating deep space for nourishment, we encourage the patient to focus on the grounding needs of the body as opposed to its garbage.” The doctor swung his arm in an arc at the shoulder joint. “It’s a long, somewhat confusing walk from the heart to the brain.”

***

It is too soon. I don’t know what else to tell the officers when they ask where they should take us. “Nowhere” is not an acceptable answer, so we direct them to the beehive. We’re not ready to thank Hannelore, Lisa, or Cyan. We’re not ready to hear their apologies. We’re not ready to cry or do anything appropriate or expected

***

“Here’s where the magic happens,” the doctor said. We were face to face with what all the science books tell you a brain—or intestines—should look like, but it was spinning. Many cylinders, filled with powder, skipped around with megaphones screeching positive mantras; some were caught in the gray grooves of the innards, which had been pasted to an enormous wheel of photographic panels. Most of the parade of cylinders that we could see—and it was getting harder to see—were using all their power to keep this wheel whirling. Dull snaps of electricity, blazing electric strings, and a general crackling surrounded the wheel. The dullness may have been due to all the fog, which even the fat light was no match for.

The panels: a photograph of Porter’s belt; a photograph of the scene of our first night in the alley; a Polaroid of Cyan; fading photographs of each of our parents. A movie on loop, like the recurring nightmare where we jump into a wheat field from a hot-air balloon that’s caught fire and are trampled by blue elk with cloud-shaped spots that stampede into a heap of human bodies. That wheel clicked hypnotically. The spinning slowed until the wheel stopped with a squeal on a picture of three blades of grass braided together. The building wavered like it wasn’t touching ground.

***

Hannelore laughs on the merry-go-round at school but Lisa pouts. “I need to practice being still.” She sticks her puffy lip out. Hannelore just moved here, so she doesn’t understand Lisa yet. “It’s good that she’s happy, though,” Cyan says. “I think it would be sad to move.”

“We could plan a party for her.” I want to but I am scared to do it by myself and I feel like a bee is stinging me all over every time. Cyan smiles and says she wants to do it with me. “It is good to be happy even if something hard happened. My mom says that a lot.”

Something is off with this memory. It didn’t used to be like this.

We find very long pieces of grass with furry ends that look like tails of cats. Cyan helps us braid them together. Lisa makes the long grass braids into a necklace that won’t break when she ties it around Hannelore’s neck.

Twenty-six adults line up. One gets a hole in their head.

Who is telling it this way?

Right after, someone’s arm starts bleeding and another one screams and falls down.

Stop. Who is telling the story this way?

Another one grabs his shoulder and red begins pushing between his fingers.

Stop.

A woman grabs her chest

stop

and falls forward and so on stop until all 26 are on the stop ground. The ground stop shakes with the deer that are coming. Stop.

***

“Do you see the smoke?” the doctor asked.

“Not yet. They must be completing work on the eyes,” the nurse said. We could hear the flap of lab coats and make out the outlines of gestures—maybe handshakes or directions—between them and the cylinders.

“Ask your doctor if Celexa is right for you,” a syrupy female recording said. The litany of side effects echoed all around. We heard “mind fog,” but it was unclear whether this was sufficient reason to call your doctor.

Does it matter? We don’t have a doctor.

When the commercial concluded, we could no longer hear the wind that had been in our ears since we’d entered the building. We couldn’t hear as many of us as usual. Which of us is gone?

Every Rori answered except Little Rori. That memory was hers, half hers, but we couldn’t hear her anywhere in it. Everything was softening around the edges.

Not softening. Melting. Disintegrating. Why didn’t it hurt?

“They must be finished with the Eustachian piping replacement,” the nurse said, just before the next commercial began.

Feathers on our lips, claws on our tongue as they mouthed the words to the Noxzema face-wash commercial.

“They must have finished ear and mouth reconstruction at the same time, then?” We heard the nurse through the crack in commercials.

They must have finished ear and mouth reconstruction at the same time, then? Our own voice, though not from our throat.

“It would seem so” —it would seem so—“but I don’t remember authorizing two work crews,” the doctor said through a tight throat, “or signing two work orders or ordering two sets of equipment”—but I don’t remember authorizing two work crews or signing two work orders or ordering two sets of equipment.

We had climbed as high as we were going to go. We walked up a clear sinus cavity, which couldn’t possibly have been ours, and stopped at the edge. Two glowing circles tinted the hazelish light and fractured it through glass pictures made of kaleidoscope parts of trees and happy birds framing a stone path leading off into the distance. Lisa herself, our little photography fairy, could not have captured more subsidized peace.

“The eyes are always the first thing a reconstruction crew thinks they’re done with,” the doctor said over the commercials (which had sprouted into whole shows).

“What do you mean?” The nurse seemed to shrug with her voice. We repeated it in our mind in the same intonation, which made it go steel drums around the edges as we were led to the sills beneath the circular windows, noticing on the way that the right was slightly less circlish than the left.

“How do you know when a kaleidoscope is broken?” The doctor asked as we snuck a view through the left window to see green but no longer any seams where the broken pieces met. He tapped the glass with the edge of his thumbnail. “Everything looks whole.” He glared through the glass like he wanted to punish some mischief.

Everything on the outside appeared complete. Maybe it even looked whole from the outside. The parts considered this and argued. I still could not hear Little Rori.

We saw a knotty olive branch where the unbandaged hand should have been. We hit play on the mind’s tape of the commercial for Humira—“…the most commonly prescribed drug for rheumatic pain.” We put our hands on the windowsill; it shivered and shook everything away from itself that was not gold. We looked back out the window; a spot on the sidewalk where one of the leaves had fallen from the olive branch was gilded (weakly?) where the leaf fell. We put our hand to our head as we watched a leaf wing up to the top story of the building—we couldn’t see if it turned gold, and no one knew what turning gold might feel like. Crashing, creaking, then gold light, and the next time we saw our mom, the fridge of our childhood, the ratty shoes we outgrew long before we got new ones, Amanda crying, they were all gashed with gold. The gold seemed gashed, too.

Amanda looked like she was still crying, but now, in the shine of healing, we didn’t hear sobs or gasps. We saw out of the building’s eyes a leaf fall into a plastic cup a streetman rattled; the cup was no fuller, but now it smoldered. We inclined to touch the gouge in the right toe and the building groaned, its creak reverberating down the crusty staircase of the spine. The worried staff rushed back to their work, herding cylinders; less than a minute later, new cylinder recruits flooded past beneath the feet, under the sinus cavity, and soon we were unable to think about the pain cruising freely along the spine.

“Structural deficiency is not easily corrected,” the nurse said after the next commercial break, tugging on some gray matter. The head got closer to the pavement; we rested on the windowsill as the sidewalk rose.

As we tipped, a knife plunged into the gut. We saw a womb-like structure, attached by a hose to the middle of the building. Thousands of tubes stuck into the dripping flesh like it was a pincushion. Several staff members attempted to manage each tube without coordinating with each other. One tube carried words to one part of the structure, another carried templates of images; one carried positivity mantras; one seemed to be laying groundwork for more flesh.

Everything was growing like mad, except the uterine flesh in the places attached to the big hose, which had turned the same hue and consistency as the sidewalk. That gray hardness was spreading up the tube attached to it and we started falling faster. A staff member tried to clear the others out of the way by instructing them to find other places to work as he frantically pulled hoses out of the graying flesh. Wind picked at my insides as they disbursed. An especially intolerable breed of pain haunted below the black hole inside us. The building stopped falling. There were cracks in the gold everywhere, flakes and chips.

***

The worst had finally happened. Our breath was choppy, like we were on a cantering horse. We counted us. We counted again. One was missing.

Count again.

No. Not everyone. Not everyone is here.

A nurse in a three-point hat that looked like it was from a costume store examined the wound, open like a question in our wrist. She lifted an individually wrapped pumice stone out of her desk drawer and started scraping it against the caked-over incision.

She produced iodine, which spread fire up our arm. She thought our shakiness was pain not fear. We didn’t correct her.

“Guests are allowed extra visitors during the holidays,” the nurse said as if she were the one the iodine was stinging.

It would make us mad if the women we used to call friends, before I started living on the streets, still thought we were. I shrugged and stayed silent as the nurse burned our wound.

She pushed her lips together, stayed between the only exit and us. She jammed a cotton ball into the heart of our wound and motioned for me to hold it there, each throb bending me further and further over, while she cleaned up. “Just in time for group.” She made me walk out of the room first and herded me down a skinny hallway to a room with a flickering light and walls that reflected back the clouds racing across the windows.

We’d make a fine group on our own. Or would have until the treatment.

The fog had still not burned off when the nurse led us to the only empty bucket chair in a full ring of them. The team thought run—first unison thing in years—and jerked both our legs, but among those of us left, none remembered how.

Riot in the highlands

by

Megan Wildhood

excerpt from a work in progress

Our body spun on a bed under a stationary ceiling fan encircled by white Christmas-tree lights. Watching it made us motion sick for the first time in our life—was it our body that was spinning, or our mind? We saw our body below from the ceiling. Our neck felt like a singular, swollen joint. A machine (labeled PROPERTY OF KING WEST MED CENTER—EXAM ROOM 7 in handwritten block letters just above its spECTrum 5000Q—MECTA Corp. embossment) hissed near our ear, like it was making secrets with the bed-table propping us up. An angel lifted off from a Christmas tree and burst into bright ash as it arced over us. We instinctively tried to tuck and cover, but one wrist and one ankle met harsh resistance and stayed pinned to the bed.

Being in two-point restraints at King West Medical Center pretty much means only one thing: involuntary commitment to the psych ward.

A large buzz hummed in the background of everywhere. We looked down and realized we could look down—we were not outside on the ground, we were not trash in a dumpster. The amount of joy that flooded us—we were not outside! We wanted to sing as we flew around the room—was almost enough to ground us back into our body. Don’t give them any more reasons to think you should be here, dear. The angry white was not the rare bird of snow but tile. An angular man passed by on a carousel made of paper cups and yellowed wallpaper. A dryer turned like it was nauseous. A fridge muttered like an empty stomach. A fridge! The back of our skull felt missing. Most other objects were too small or too large to be seen. We tasted clay. The fan started to move, slicing dark into thick belts.

***

“Your husband was perfect.” It’s only okay that Cyan says this so soon, the same day of Porter’s death, because she’s been our best friend since kindergarten.

***

A man in a lab coat walked into the room, which was so white it would show any iota of dirt. A door swiveled open to let in people made of parchment dressed like TV doctors. Our neck loosened. Pebbles dropped from our ears and rolled around in our neck. The side of our head filled with a lively pain. One doctor said our name, but his voice sounded like it had to get through water. What he said wasn’t to us. “This is enough for today. She’s quieted down nicely.” The words moved in pieces. The buzz softened but pressurized, like it had been stuffed into our mind. His pointy fingers prodded the goose egg on the very center of the top of our head. The hole in the middle of our brain, which also felt like it was in the middle of our heart, was new, too. Things were falling into our eyes as we looked at them, faster than our brain could name them.

We could not raise our arms or bend them. Same with our legs. Our head was flopping side to side without direction from inside it. This was not exhaustion. Cold, hard bands clamped our wrists and ankles to within an inch of the table. The pillow smelled like burnt sage and cedar as it started to swallow our head. A crack started in the ceiling, splintered into a million more.

The man and a nurse start-stopped around the room like an old movie reel. They took our fingerprints and scanned our retinas and led us, still lying down, to a 5.11-story building adorned with our auburn hair and our wide hips. The top floors looked to be separating from the body of the structure. It wore our old uniform: a V-neck, navy-blue sweater vest with “Metro Transit” sewn in thick red thread over a T-shirt, stiff green in need of a stiff drink, and starched navy pants. Its wrist was wrapped hard in medical gauze. We entered through a latched gash we didn’t know we had in the right toe (not the one with the missing nail). Once the door closed, it sounded like a mass shooting in an amphitheater: more construction than around the city of Seattle. A staff member switched on a gas lantern and guided us up what turned out to be a long, steep flight of stairs.

***

“Photovoltaic,” Hannelore says, sitting on the orange couch with Lisa. Cyan stands closer and closer to us. Lisa hinges her face toward Hannelore with her jaw; her eyes—the same color as her hair before she dyed it black—stay on Cyan. Hannelore breathes slowly, trying to be silent like she feels guilty she can breathe, darting her gaze between Cyan, Lisa, and the widow. We are the widow. We are not the person who was friends with Hannelore, Cyan, and Lisa for all those years before they went off to live real lives. We are no longer that person, but they, just like Porter, left first. They all left first.

***

The whole building lurched as we passed through a hallway that seemed like a morgue and smelled like lemon. The passageway narrowed in places where the walls became swollen, and ended in a right angle at an ankle where the stairs were stiff. We had to cross over another hinge point at the knee, enlarged and shouting red, as the staircase widened and the rush of strong rivers flushed past us all around, whooshing like speeding buses crossing a bridge.

We climbed behind the presumed doctor and the nurse to where a stomach should have been. Just darkness so black it was blue. So black that light could not escape. An orange-clad construction crew exchanged this dark for seething flesh, piece by piece; the smell of Cheetos seized our saliva glands and panged in our jaw. Hunger like a gong doubled most of us over. The fibers of the new stomach had no substance; they could hold almost nothing except stories of holding almost nothing.

***

The police cut down the body. It doesn’t end its ending. The officer who catches it grunts like it weighs something. But it is made of gauze.

***

The brusque tick of an old-timey movie projector on the pistoning crimson above the stomach made us twitch. Amanda, eight, rifles through boxes our parents labeled “storage”. No food in the boxes. Amanda tosses their contents onto the living room floor and cries too loudly not to get in trouble. Our arms and hands and stomach and butt tensed up as we struggled to stack them, hoping to avoid punishment ourself. Neither parent comes. We find a purple and gold photo album, blue and pink and yellow flowers drawn on it with chalk, maybe; A Girl and Her Vacations calligraphed across the top of the cover. The back half of the book is empty; the front half has us with Amanda, Mom, Dad and, at the very beginning, Beauty, our beloved black boxer. Cyan came with us to the beach that day. Hannelore finally got into a tent with us. Lisa captured it. Hannelore’s eyes were so green it’s a wonder everything she looked at wasn’t the same color. How we got a copy of that photo isn’t documented anywhere, internal or external. Several shots of the four of us at various ages, outside under a trellised lamentation of clouds. A shot of Amanda’s hand connected to Dad’s hand connected to Mom’s shoulders connected to strong arms connected to our left hand, which the juvenile RA had already started to colonize. The edges of the photos, of the album, of the room, are all beginning to melt like wax.

***

Six inches from our nose, stomach fibers twisted and tightened. There was no memory of this. “Don’t worry, many memories are stored in the brain, too,” the nurse said, hovering above us in immaculate heels that could aerate a crop field. “We can search there, too, when we get there.” Her voice was too gelatinous for her stringy body. Her three-point hat cast a chilling shadow of a human with an insufficient head.

***

If Porter wrote a note, it is never found.

***

Our stomach churned through acid like Amanda through boxes. “It’s okay to not remember,” the doctor said, measuring and muttering.

Sand poured down the stairs. We’d spent significant time at a beach only once: with Cyan, the stressfully loud and relentless ocean, the messy piles of long-dead trees, seaweed slick as ice; how sand held the sun long after the day buckled. The sand falling down our knees was red and white and hotter than any day could have made it, no matter how immortal that day was in our mind.

“Have you ever seen that photo album before?” The doctor pointed into a new scene (a wedding album?), white with rhinestones and multicolored seed beads splattered in the right corner and all along the spine. “Family vacation seems unlikely, yes,” the nurse nodded and wrote something on a legal pad pinned to a clipboard in her hand. We hadn’t said anything out loud, we thought. “Correct.” The doctor clicked his tongue. The whole building spasmed again.

We trudged up more stairs, passed the black hole that had to be deeper than the building. We saw the light, thick as water, before we turned the corner to the last flight on this level: the central hub of the building. Doors slammed rhythmically somewhere close, which was oddly soothing, the way human sounds are at night when you think you’re alone and don’t want to be. Several shadows—some actual monsters, some with Amanda’s face or Cyan’s voice or Lisa’s hugs or Hannelore’s latent lost shit— flitted by and we felt it in our heart.

“It looks like the voltage I guessed wasn’t too far off.” The doctor tapped a pencil on the edge of a clipboard. “By keeping the light thick,” the doctor said, “we ensure buoyancy in the heart and mind.”

“Essential to recovery,” the nurse said like it was a recording the two of them made long ago.

“Many people undergoing mental collapse find they can’t eat or don’t wish to,” the doctor said.

“By creating deep space for nourishment, we encourage the patient to focus on the grounding needs of the body as opposed to its garbage.” The doctor swung his arm in an arc at the shoulder joint. “It’s a long, somewhat confusing walk from the heart to the brain.”

***

It is too soon. I don’t know what else to tell the officers when they ask where they should take us. “Nowhere” is not an acceptable answer, so we direct them to the beehive. We’re not ready to thank Hannelore, Lisa, or Cyan. We’re not ready to hear their apologies. We’re not ready to cry or do anything appropriate or expected

***

“Here’s where the magic happens,” the doctor said. We were face to face with what all the science books tell you a brain—or intestines—should look like, but it was spinning. Many cylinders, filled with powder, skipped around with megaphones screeching positive mantras; some were caught in the gray grooves of the innards, which had been pasted to an enormous wheel of photographic panels. Most of the parade of cylinders that we could see—and it was getting harder to see—were using all their power to keep this wheel whirling. Dull snaps of electricity, blazing electric strings, and a general crackling surrounded the wheel. The dullness may have been due to all the fog, which even the fat light was no match for.

The panels: a photograph of Porter’s belt; a photograph of the scene of our first night in the alley; a Polaroid of Cyan; fading photographs of each of our parents. A movie on loop, like the recurring nightmare where we jump into a wheat field from a hot-air balloon that’s caught fire and are trampled by blue elk with cloud-shaped spots that stampede into a heap of human bodies. That wheel clicked hypnotically. The spinning slowed until the wheel stopped with a squeal on a picture of three blades of grass braided together. The building wavered like it wasn’t touching ground.

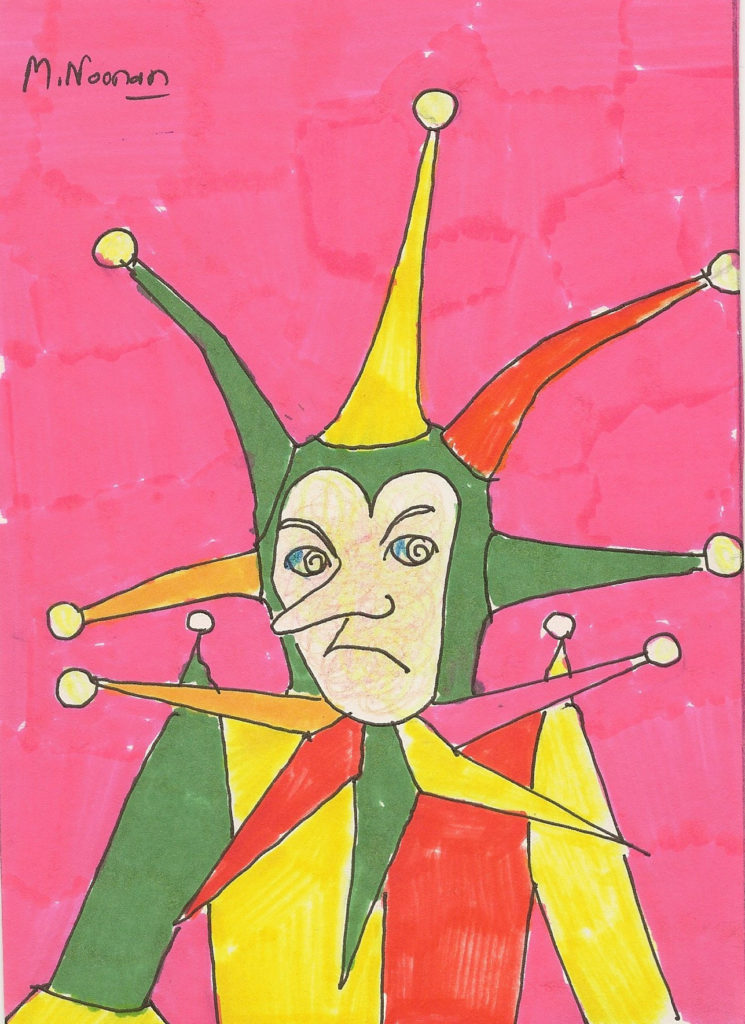

A Jester, by Michael Noonan

***

Hannelore laughs on the merry-go-round at school but Lisa pouts. “I need to practice being still.” She sticks her puffy lip out. Hannelore just moved here, so she doesn’t understand Lisa yet. “It’s good that she’s happy, though,” Cyan says. “I think it would be sad to move.”

“We could plan a party for her.” I want to but I am scared to do it by myself and I feel like a bee is stinging me all over every time. Cyan smiles and says she wants to do it with me. “It is good to be happy even if something hard happened. My mom says that a lot.”

Something is off with this memory. It didn’t used to be like this.

We find very long pieces of grass with furry ends that look like tails of cats. Cyan helps us braid them together. Lisa makes the long grass braids into a necklace that won’t break when she ties it around Hannelore’s neck.

Twenty-six adults line up. One gets a hole in their head.

Who is telling it this way?

Right after, someone’s arm starts bleeding and another one screams and falls down.

Stop. Who is telling the story this way?

Another one grabs his shoulder and red begins pushing between his fingers.

Stop.

A woman grabs her chest

stop

and falls forward and so on stop until all 26 are on the stop ground. The ground stop shakes with the deer that are coming. Stop.

***

“Do you see the smoke?” the doctor asked.

“Not yet. They must be completing work on the eyes,” the nurse said. We could hear the flap of lab coats and make out the outlines of gestures—maybe handshakes or directions—between them and the cylinders.

“Ask your doctor if Celexa is right for you,” a syrupy female recording said. The litany of side effects echoed all around. We heard “mind fog,” but it was unclear whether this was sufficient reason to call your doctor.

Does it matter? We don’t have a doctor.

When the commercial concluded, we could no longer hear the wind that had been in our ears since we’d entered the building. We couldn’t hear as many of us as usual. Which of us is gone?

Every Rori answered except Little Rori. That memory was hers, half hers, but we couldn’t hear her anywhere in it. Everything was softening around the edges.

Not softening. Melting. Disintegrating. Why didn’t it hurt?

“They must be finished with the Eustachian piping replacement,” the nurse said, just before the next commercial began.

Feathers on our lips, claws on our tongue as they mouthed the words to the Noxzema face-wash commercial.

“They must have finished ear and mouth reconstruction at the same time, then?” We heard the nurse through the crack in commercials.

They must have finished ear and mouth reconstruction at the same time, then? Our own voice, though not from our throat.

“It would seem so” —it would seem so—“but I don’t remember authorizing two work crews,” the doctor said through a tight throat, “or signing two work orders or ordering two sets of equipment”—but I don’t remember authorizing two work crews or signing two work orders or ordering two sets of equipment.

We had climbed as high as we were going to go. We walked up a clear sinus cavity, which couldn’t possibly have been ours, and stopped at the edge. Two glowing circles tinted the hazelish light and fractured it through glass pictures made of kaleidoscope parts of trees and happy birds framing a stone path leading off into the distance. Lisa herself, our little photography fairy, could not have captured more subsidized peace.

“The eyes are always the first thing a reconstruction crew thinks they’re done with,” the doctor said over the commercials (which had sprouted into whole shows).

“What do you mean?” The nurse seemed to shrug with her voice. We repeated it in our mind in the same intonation, which made it go steel drums around the edges as we were led to the sills beneath the circular windows, noticing on the way that the right was slightly less circlish than the left.

“How do you know when a kaleidoscope is broken?” The doctor asked as we snuck a view through the left window to see green but no longer any seams where the broken pieces met. He tapped the glass with the edge of his thumbnail. “Everything looks whole.” He glared through the glass like he wanted to punish some mischief.

Everything on the outside appeared complete. Maybe it even looked whole from the outside. The parts considered this and argued. I still could not hear Little Rori.

We saw a knotty olive branch where the unbandaged hand should have been. We hit play on the mind’s tape of the commercial for Humira—“…the most commonly prescribed drug for rheumatic pain.” We put our hands on the windowsill; it shivered and shook everything away from itself that was not gold. We looked back out the window; a spot on the sidewalk where one of the leaves had fallen from the olive branch was gilded (weakly?) where the leaf fell. We put our hand to our head as we watched a leaf wing up to the top story of the building—we couldn’t see if it turned gold, and no one knew what turning gold might feel like. Crashing, creaking, then gold light, and the next time we saw our mom, the fridge of our childhood, the ratty shoes we outgrew long before we got new ones, Amanda crying, they were all gashed with gold. The gold seemed gashed, too.

Amanda looked like she was still crying, but now, in the shine of healing, we didn’t hear sobs or gasps. We saw out of the building’s eyes a leaf fall into a plastic cup a streetman rattled; the cup was no fuller, but now it smoldered. We inclined to touch the gouge in the right toe and the building groaned, its creak reverberating down the crusty staircase of the spine. The worried staff rushed back to their work, herding cylinders; less than a minute later, new cylinder recruits flooded past beneath the feet, under the sinus cavity, and soon we were unable to think about the pain cruising freely along the spine.

“Structural deficiency is not easily corrected,” the nurse said after the next commercial break, tugging on some gray matter. The head got closer to the pavement; we rested on the windowsill as the sidewalk rose.

As we tipped, a knife plunged into the gut. We saw a womb-like structure, attached by a hose to the middle of the building. Thousands of tubes stuck into the dripping flesh like it was a pincushion. Several staff members attempted to manage each tube without coordinating with each other. One tube carried words to one part of the structure, another carried templates of images; one carried positivity mantras; one seemed to be laying groundwork for more flesh.

Everything was growing like mad, except the uterine flesh in the places attached to the big hose, which had turned the same hue and consistency as the sidewalk. That gray hardness was spreading up the tube attached to it and we started falling faster. A staff member tried to clear the others out of the way by instructing them to find other places to work as he frantically pulled hoses out of the graying flesh. Wind picked at my insides as they disbursed. An especially intolerable breed of pain haunted below the black hole inside us. The building stopped falling. There were cracks in the gold everywhere, flakes and chips.

***

The worst had finally happened. Our breath was choppy, like we were on a cantering horse. We counted us. We counted again. One was missing.

Count again.

No. Not everyone. Not everyone is here.

A nurse in a three-point hat that looked like it was from a costume store examined the wound, open like a question in our wrist. She lifted an individually wrapped pumice stone out of her desk drawer and started scraping it against the caked-over incision.

She produced iodine, which spread fire up our arm. She thought our shakiness was pain not fear. We didn’t correct her.

“Guests are allowed extra visitors during the holidays,” the nurse said as if she were the one the iodine was stinging.

It would make us mad if the women we used to call friends, before I started living on the streets, still thought we were. I shrugged and stayed silent as the nurse burned our wound.

She pushed her lips together, stayed between the only exit and us. She jammed a cotton ball into the heart of our wound and motioned for me to hold it there, each throb bending me further and further over, while she cleaned up. “Just in time for group.” She made me walk out of the room first and herded me down a skinny hallway to a room with a flickering light and walls that reflected back the clouds racing across the windows.

We’d make a fine group on our own. Or would have until the treatment.

The fog had still not burned off when the nurse led us to the only empty bucket chair in a full ring of them. The team thought run—first unison thing in years—and jerked both our legs, but among those of us left, none remembered how.

Megan Wildhood is a writer, editor, and writing coach who helps her readers feel seen in her monthly newsletter, poetry chapbook Long Division (Finishing Line Press, 2017), her forthcoming poetry collection, Bowed As If Laden With Snow (Cornerstone Press, May 2023), as well as Mad in America, The Sun, and elsewhere. You can learn more about her writing, working with her, and her mental-health and research newsletter at meganwildhood.com.